Cyber Espionage Among Friends

Russia and China are well aware of each other's APT activities but choose to deal with them quietly.

While espionage among rivals draws most of public attention, one should not forget that like-minded nations spy on each other, too. Although this area remains understudied, there are plenty of historical examples of allies and friendly countries collecting intelligence on each other including for political, military, and economic purposes.

This also holds true in cyberspace — in fact, digital technologies arguably offer more opportunities for espionage among friends.

Despite their declared no-limits partnership and close alignment on international information security initiatives, Russia and China are aware of each other’s cyber espionage efforts. This is evidenced by Chinese cyber security researchers tracking a Russian APT group, and vice versa. Yet, unlike among rival states, neither in Russia, nor in China concerns about each other’s APT activities translate into public accusations at the political or diplomatic level.

A Very Vindictive APT

In the beginning of February, Chinese cyber security company QiAnXin released its annual report on APTs. The report puts together findings from multiples threat intelligence reports as well as QiAnXin’s own findings.

The report features a section (P. 16-17) on APT-Q-77 — this is QiAnXin’s monicker for APT29/CozyBear/Nobelium/TheDukes, a group considered to be “related to the government of a certain country in Eastern Europe.”

In short, while QiAnXin does not directly attribute APT-Q-77 to Russia, it essentially considers it the same group that is widely believed to be connected to Russia and that is publicly attributed by the United States.

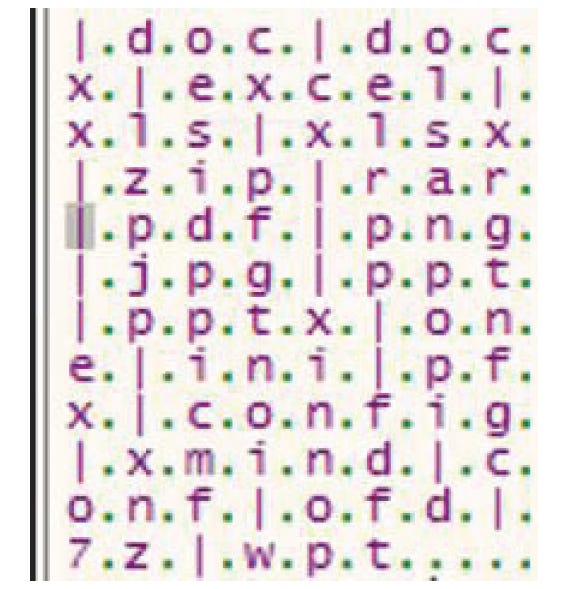

According to the report, in the second half of 2023 APT-Q-77 targeted the chip industry in China. The attackers first deployed Cobalt Strike, then used a plugin to collect file information — QiAnXin researchers compare this idea (i.e. collecting only file information) to that of APT37. File information was then AES-encrypted and uploaded to the C2 server. Subsequently a Rust trojan was deployed onto victim computers using Cobalt Strike, maybe to upload specified files — but QiAnXin’s analysis stops there because the trojan was embedded in the memory of the system process and its operations were hard to detect.

Another interest of APT-Q-77, as reported by QiAnXin, was China’s energy sector, specifically its energy projects in Central Asia, North Asia, and Southeast Asia. The report features a screenshot of an LNK decoy sent to target organizations in a particular region in China which was followed by the uploading of malware (apparently attributed to APT-Q-77) on VirusTotal from the same region.

QiAnXin researchers have been tracking APT-Q-77 since 2022 when they published a blogpost on the group’s activities targeting Italy using Slack. It was noted that the attack had not been observed in China.

But in its 2022 annual report (P. 22) QiAnXin wrote that in the end of 2022 it discovered a group it had never seen before (dubbed APT-Q-77) whose attack activities were very frequent, targeting in particular energy targets related to China in Central Asia. Other targets, per keywords, included government and military industry. The report claimed that the QiAnXin team captured one 0-day vulnerability, four trojans, and six loaders used by APT-Q-77; the group used Cobalt Strike and not-seen-before trojans written in Rust.

In its mid-year report last year (P. 7), QiAnXin revealed that it traced back APT-Q-77 activities back to July 2022 when it was sending spear-phishing emails with CHM, ISO (IMG), and LNK to military sector targets. The attack chain included a Cobalt Strike loader in the first stage, the second stage loader, and the deployment of a Rust trojan in the third stage.

QiAnXin claimed that if successfully blocked APT-Q-77 in the end on 2022 — after that, in January 2023, the attackers allegedly accessed the official website of QiAnXin Threat Intelligence Center to study the firm’s publicly available reports. According to QiAnXin’s assessment, the group is composed of 8-9 members, which allowed it to use different tools and techniques against different targets. The report also suggests, based on closed-source threat intelligence, that APT-Q-77 used a Rust trojan to penetrate the medical chemistry field in Western countries.

Not only did APT-Q-77 browse QiAnXin’s website, it also decided to impersonate the cyber security firm in a phishing campaign. The attackers sent a forged email under the guise of QiAnXin urging recipients to install a toolkit presumably to detect and remove malware of another hacking group, OceanLotus. QiAnXin described the new payloads created for the campaign and noted that the C2 domain the trojan communicated with also mimicked the firm’s official website. The blogpost featured some additional details about the earlier phishing campaign from 2022 and had a few words about the language of the emails: apparently overall there was not much problem, but some sentences seemed to be machine-translated and were not very clear.

QiAnXin was quite surprised by how much attention it received from APT-Q-77 and how “vindicative” the group was, even wondering whether the group could have been mimicking a known organization.

The Main Cyber Spies

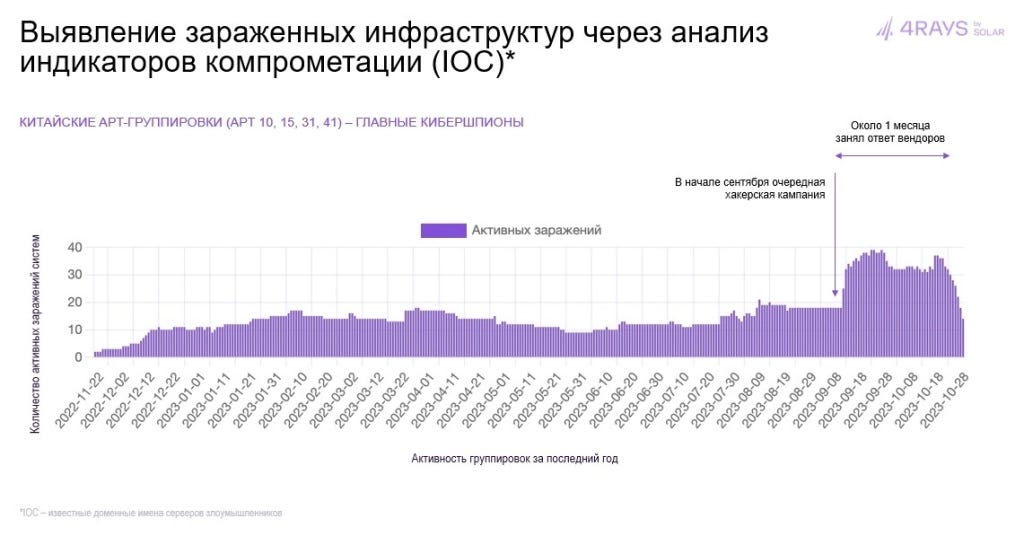

In November 2023, Russian cyber security firm Solar (previously known as Rostelecom Solar) reported that among APTs operating in Russian Chinese APTs were the most active ones (followed by Lazarus).

The accompanying slide referred to the Chinese APTs (APT10, APT15, APT31, APT41) as “the main cyber spies.”

Solar made this assessment based on “telemetry data from Rostelecom’s largest in Russia network of sensors and honeypots.” The press-release highlighted a new cyber espionage campaign launched by the Chinese APTs in September 2023 that was infecting 20-40 organizations daily before it was detected by cyber security vendors a month later.

What is remarkable about this assessment is that Solar unequivocally linked APTs to China. But in general reports about Chinese APT activities are hardly news in the Russian cyber security industry. Sometimes connection to China is made clear, but more often researchers attribute attacks to groups that are known as Chinese APTs without directly mentioning the country.

In 2019-2020, Solar, together with the National Computer Incident Response Coordinating Center (NCIRCC, part of the Federal Security Service), investigated and thwarted a major espionage campaign by a Chinese actor — attributed by other researchers to TA428 — against Russian public sector (more about this in the next section). In 2022, Igor Zalevskiy, head of cyber incident investigations at Solar, gave a presentation on tools, tactics, and techniques of Chinese APTs detected by the firm in the previous year.

Solar is not alone, other Russian firms investigated a variety of attacks attributed to China-linked APTs over the recent years.

In 2021, Positive Technologies identified APT31 attacks targeting Russia (as well as Belarus, Canada, and the United States). And in 2022, it detected attacks on Russian government agencies by Tonto group. The same campaign apparently also targeted employees of Group-IB, and in its write-up the company described Tonto Team as a nation-state APT and “a cyber espionage threat actor that is believed to originate from China”.

In 2022, Kaspersky reported on a campaign likely carried out by TA428 that targeted governments as well as defense sector in Russia, along with Belarus, Ukraine, and Afghanistan.

Gentlemen Don't Talk About Reading Each Other's Mail

To sum up, cyber security researchers in Russia track APT groups from China, and vice versa. Does this translate into diplomatic action? In short, no, at least not publicly.

Both Russia and China are ambiguous about public attribution of cyber attacks. They dismiss Western accusations as baseless and politicized. Yet both countries respond with their own accusations against the United States, essentially engaging in quasi-attribution: for several years, China has been referring to the United States as the “Empire of Hacking,” while Russian officials claim that the the U.S. Cyber Command as well as other Western agencies coordinate Ukrainian hackers attacking Russia.

Some of these accusations are based on findings made by private companies. For instance, in June 2023 Russia’s Federal Security Service issued a statement on U.S. intelligence campaign targeting iPhones — largely basing their assessment on Kaspersky’s research into Operation Triangulation that avoided attributing the campaign to any particular actor.

So far industry reports about Chinese APTs in Russia or Russian APTs in China have not been exploited for political or diplomatic purposes in neither country.

One instructive example that came very close to this is a 2021 technical report published in Russia by NCIRCC and Solar. The public version of the report described a series of targeted attacks against Russian government agencies. Although the report avoided attribution, Nikolay Murashov, Deputy Head of NCIRCC, commented at the time of its release: “Based on the complexity of the tools and methods used by the attackers, as well as the speed of their work and the level of training, we have reason to believe that this group possesses resources on par with a foreign intelligence service.”

Almost a month later, Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade of SentinelOne made an argument that the campaign that NCIRCC and Solar reported was in fact linked with a threat actor of Chinese origin, TA428. Two months later, in August 2021, Russian branch of Group-IB echoed this conclusion and suggested that two Chinese state sponsored groups, TA428 and TaskMasters, could have been behind the attacks on Russian government agencies.

In 2023, Vladimir Dryukov, Head of Solar’s security operations center Solar JSOC, explained that Solar researchers were well aware of the origin of the APT, but made a decision to strip the public version of the report of attribution for political reasons; yet they kept attribution in a second, non-public report distributed by NCIRCC via its network. (In 2022, Igor Zalevskiy of Solar JSOC also mentioned the joint report with NCIRCC in his talk on Chinese APTs.)

This case illustrates that the Russian authorities (or at least security agencies) are informed about espionage activities of Chinese APTs and that such activities are not tolerated. In fact, the report was a culmination of more than year-long efforts to expel the attackers from government networks. Even its unprecedented publicity (albeit lacking the mention of a specific country) was probably intended to signal that such attacks are not OK.

At the same time due to political considerations, the problem was not escalated to the diplomatic level. Cyber espionage by a friendly country is a concern, but it is dealt with at the professional level and should not trump the larger partnership.

While one should be cautious when generalizing from this example, it is likely that similar factors are at play in China, too.

What makes this picture even more complex, though, is that unlike most other states Russia and China share a legally binding commitment that they should avoid precisely the type of interference with each other’s information systems that APTs are engaged in.

This pledge is enshrined in two agreements: the 2009 Shanghai Cooperation Organization Agreement on Cooperation in Ensuring International Information Security and the 2015 bilateral Agreement on cooperation in this area. Both feature a nearly identical commitment not to hack each other.

For instance, part of Article 4 (General principles of cooperation) of the Russian-Chinese agreement reads:

“Each Party shall have an equal right to the protection of the information resources of its state from unlawful use and unauthorized interference, including from computer attacks on them.

Each Party shall not take such actions in relation to the other Party and shall assist the other Party in realizing the aforementioned right.”

Do these agreements have any effect? It would be hard to argue that cyber espionage activities by state-sponsored APTs do not constitute a breach of this pledge. One possible way to square this circle is to act as if these are, in fact, not state-sponsored groups, just sophisticated and well resourced criminals (in his announcement of the 2021 NCIRCC report, right after he compared the attackers to a foreign intelligence service, Nikolay Murashov referred to them as “highly skilled cyber criminals”).

Another possibility is that the no-hacking clause is not viewed as iron-clad or all-encompassing.

It is also possible that compliance issues are raised between diplomats and security officials in private — but one would assume that this should result in the halt of activities in question (it would be quite rude if, for instance, Russia privately drew China’s attention to a particular APT only to see it reemerge after a while), and there is no evidence of this yet, quite the contrary.

Conclusion

Borrowing from Florian Egloff, one can analytically split attribution of APT activities into sense-making and meaning-making processes. The former refers to finding out what happened (through private sector and intelligence investigations), while the latter involves figuring out what to do about it at the national security level.

It is no wonder that the meaning-making part of this would look differently when dealing with adversaries or friends. Over the past decade the United States has publicly attributed cyber attacks to only four states (China, DPRK, Iran, Russia) deemed adversaries, while it is probably safe to say that these were not the only nations active in U.S. networks.

The Russian-Chinese dynamics described here demonstrates what meaning-making can produce when addressing cyber espionage concerns among friendly nations. Unsurprisingly, it is not naming and shaming. Rather cyber espionage is dealt with in a depoliticized fashion, at the professional rather than political level.

Whether this situation is sustainable is an open question. The sectors that are reportedly targeted in each country are very sensitive, while the line between what is acceptable and what is not seems blurry. These problems are overridden by the top-level partnership, but if neglected they would generate tension and limit how much the two countries can cooperate on cyber issues.