Nationalization of Cyber Threat Intelligence

Cyber threat intelligence has evolved primarily as a private domain driven by cyber security vendors and researchers. Is this about to change?

Introduction

Over its not-so-long history cyber threat intelligence has been shaped primarily by the private sector: researchers, cyber security firms, tech giants. This is obvious when we look at this field today. It’s vendors that come up with confusing and ever-mutiplying taxonomies of threat actors. Cyber security industry and to a lesser degree academia are the main source of the cumulative body of knowledge, in the form of technical reports about what these actors do and how to defend against them. Threat intelligence is sold to other businesses in the form of private briefs, feeds, specialized software, etc.

Of course this was not all done by the private sector alone. The now ubiquitous term APT was originally coined by U.S. military. The cyber security industry benefited from the expertise brought by former military, law enforcement, and intelligence officers as well as from public and non-public information sharing. Still, today cyber threat intelligence is largely a form of business, not only in the United States and the West more generally but in other parts of the world, too, including Russia and China.

But is it the only possible way? Can—or rather will—threat intelligence become less private? In times when cyber threats get more serious and are increasingly viewed as a national security concern, can this field be ‘nationalized’ by the governments? After all, the line between threat intelligence and (counter) intelligence is blurry.

Here I want to reflect upon several recent publications that are not directly related but all seem to highlight different aspects of the trend that I would refer to as the nationalization of cyber threat intelligence—in the sense of giving it national character, not necessarily national ownership.

These publications include:

The rise of responsible behavior: Western commercial reports on Western cyber threat actors, an academic article by Tel Aviv University scholars Lior Yoffe, Eviatar Matania, Udi Sommer;

Call Them What They Are: Time to Fix Cyber Threat Actor Naming, an opinion piece by former director of CISA Jen Easterly and founding head of UK NCSC Ciaran Martin;

The advisory by the Dutch intelligence agencies on Laundry Bear, a supposedly new Russian threat actor;

Operation Futile: Investigation report on Cyberattacks launched by Taiwan ICEFCOM and its affiliated APT actors, a joint report by China’s National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center (CVERC) and Qihoo 360.

Let’s look at them one by one.

Geopolitical Considerations

Lior Yoffe, Eviatar Matania, and Udi Sommer examine the decline Western commercial reports on Western threat actors. This trend is obvious for those in the field, but the authors provide solid analysis to illustrate and explain it.

The main explanation for this decline, according to their findings, has to do with geopolitical considerations. In the early days of cyber threat intelligence (the so-called ‘age of innocence’) global cyber community (with Western firms as its prominent part) was defending globalized businesses and was not so much concerned by the borders. In that context, it was OK to take a neutral stance and treat all cyber threats equally, so reporting on threat actors from one’s own camp was not a big problem.

As the 2010s progressed, cyber threats kept growing, governments increasingly viewed them through the national security lens, while interstate rivalry reignited—including in cyberspace. The cyber security industry now had to take these geopolitical considerations into account when reporting on threat actors.

“Concurrently, private-sector firms in Western states have persistently encountered threats emanating from actors within the Western geopolitical sphere itself. These corporations have thus found themselves compelled to balance their immediate commercial interests with broader geopolitical ramifications, recognizing progressively their intrinsic role within contemporary cyber conflicts. As a result, we argue that such awareness fostered a more strategically sophisticated and nuanced approach to cybersecurity operations, fundamentally influencing corporate decision-making, particularly in terms of investigating and publicly disclosing cyber activities attributed to Western threat actors. Whether driven by patriotism, the imperative to preserve market access within Western economies, or additional business-oriented incentives, geopolitical considerations assumed heightened importance in shaping corporate strategies. This shift highlights the intertwined nature of cybersecurity operations, commercial firms and international political dynamics, reflecting a broader trend in which private sector entities must increasingly navigate intricate geopolitical landscapes while addressing cyber threats as part of their mission and responsibility to protect their customers.”

The authors probe several alternative explanations as well, but I think that they rightly identify geopolitical considerations as the main one. They are closely intertwined with business decision-making. As government get more concerned about cyber threats they increasingly see cyber security companies in their companies as an element of national power. Firms benefit from it through government contracts and other types of support. But this also changes incentives for threat reporting: what would you gain from releasing a report about your government’s cyber operations?

While the authors focus on Western commercial reports, this trend is not limited to the West. It also holds true for Russian cyber security firms. In the 2010s, it was not only that Symantec was reporting on Stuxnet and Strider. Russia-based firms with global ambitions were largely adopting the same approach and treated all threat actors the same. Kaspersky was exposing Dukes and Turla and Positive Technologies researchers shared their findings on Gamaredon attacks on Ukraine. Obviously, since the start of the war in 2022, Russian firms have been busy defending Russian organizations and no longer publish reports on Russia-linked threat actors.

To generalize, cyber security firms tend not to report on threat actors linked with their or closely allied governments. Calling this alone the nationalization is probably a stretch too far, but at least this means some sort of alignment with national security priorities.

Naming the Threat

For an outsider, the naming of threat actors of hacker groups is, to put it mildly, puzzling. The same actor can be referred to by dozen or more different names. Lazarus was historically referred to by about 30 monikers including aliases from the vendors and monikers used by the group itself.

Does it have to be this way? The current situation with multiple naming conventions is the product of the cyber security industry motivated by the need to share information among defenders but to a greater degree by marketing concerns.

The confusion this creates is well understood among the professionals, and there are attempts to make some improvements. Most recently, CrowdStrike and Microsoft agreed to harmonize cyber threat attribution. For the time being each company will continue to use its own taxonomy, but the first step is to make a shared spreadsheet with deconflicted names. Google and Palo Alto join this effort, too.

These efforts are welcome but they don’t go far enough, argue former heads of U.S. and UK cyber agencies, Jen Easterly and Ciaran Martin. In a co-authored piece they lament the current approach to threat actor attribution as misleading and favorable for the attackers.

“It’s time we stopped naming these groups in ways that mystify, glamorize, or sanitize their nefarious activities. Fancy Bear isn’t a cartoon villain—it’s Russian military intelligence. Charming Kitten isn’t a meme-worthy hacker collective—it’s Iranian state-sponsored espionage. These actors don’t deserve clever names. Calling them dirtbags would frankly be more appropriate, or if creative branding is aimed at making them more memorable, we’d suggest names like Scrawny Nuisance, Weak Weasel, Feeble Ferret, or Doofus Dingo. But the truth is, we should aim for accuracy over branding. And when attribution is clear, we should say so: China, Russia, Iran, North Korea. Calling them by name isn’t inflammatory—it’s clarifying for the cybersecurity community and the public it seeks to defend.”

The solution, according to two former senior officials, could be the greater involvement of governments in this process. This doesn’t mean that the government would make the use of one naming convention mandatory, but there are multiple ways in which it can create incentives for standardization:

“The incentives to address this issue are weak, but smart policy design could change that. Most importantly, governments—which possess extensive visibility through intelligence, law enforcement, and national cyber defense capabilities—could promote standardization by cutting through bureaucracy and being much more agile in attributing attacks, working together and with relevant vendors to be “first to market” with confirmed attribution, using universal, non-glamorized naming taxonomies. Public-private threat-sharing programs could formally adopt and reward adherence to such standardized naming conventions. Regulators might incorporate naming clarity into emerging cybersecurity labeling schemes, such as those being developed for consumer Internet of Things (IoT) devices in the European Union and United States. Even modest steps—like encouraging alignment in public-sector contracts or through cyber insurance underwriting criteria—could begin to shift norms. The goal isn’t to penalize creativity; it’s to stop the branding of adversaries at the expense of clarity, coordination, and defense.”

The governments, especially the United States, are already involved in threat actor attribution through official accusations linking aliases used by vendors to specific military or intelligence units, thus validating researchers’ findings. But so far this had little to do with standardization of naming systems. A greater involvement in this process, proposed by Easterly and Martin, could ultimately make the government the ultimate deconflicting authority on these matters and thereby to some degree shift the naming power away from the private sector.

Moving forward, what can nationalized threat intelligence look like assuming that private firms would still play a key role in defending against cyber threats? One option is for the government to become the main source of threat intelligence and thus guide the private sector. Another option is for the government to be the main convener and to deliberately use private sector expertise to achieve specific national security aims.

Leading with Intelligence

The idea of the government leading with cyber threat intelligence is intuitively simple since that’s what governments are used to doing when it comes to other types of intelligence. Yet, when it comes to cyber threats governments most of the time do not come forward by being the first ones to reveal new evidence. Most threat actors were first identified—and named—by the private sector.

However a recent public release from the Netherlands demonstrates that governments can actually be proactive. In late May, two Dutch intelligence agencies, the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) and Military Intelligence and Security Service (MIVD), put out a (semi-)technical report on a new threat actor Laundry Bear allegedly linked to Russia.

What makes this report unusual is that it’s a rare occasion where a government describes a new threat actor. Moreover, AIVD and MIVD took the liberty of naming the new APT the way they wanted—surprisingly, they chose the CrowdStrike animal-themed convention, probably because ‘Bears’ have a strong association with Russia thanks to extensive media coverage post-2016.

A conventional way would be for a threat intelligence firm to release it first and credit the government for their assistance. In this case, the Dutch report was followed by the one from Microsoft.

If we take this single case as a model, we can see how government agencies can assume a more central place in the production of threat intelligence by being the first ones to identify new threat actors, campaigns, or the evolution of tactics, techniques, and procedures. This would not involve complete nationalization since private companies would continue to play an important role in defending organizations and nations, but the government’s power to shape the conversation and understanding of threat landscape would increase.

Using Threat Intelligence Strategically

The other possible model of nationalized threat intelligence was recently illustrated by China. In early June, CVERC and Qihoo 360 put out a joint report on hacker groups allegedly linked to Taiwan and more specifically to its Information, Communications and Electronic Force Command (ICEFCOM).

It’s not the first time that CVERC, China’s specialized agency authorized to respond to computer virus emergencies, releases a report on foreign cyber threat, often with the help of Qihoo 360, a private cyber security firm.

What makes this publication unique is that for the first time it combines four elements:

technical analysis of threat actors’ activity—while some previous CVERC reports were criticized for their lack of technical details and reliance on old leaks, this one features some decent analysis and even lists relevant IOCs;

political accusation against Taiwan, the Democratic Progressive Party, and the United States;

arrest warrant and bounty for 20 Taiwanese citizens allegedly linked to threat actors;

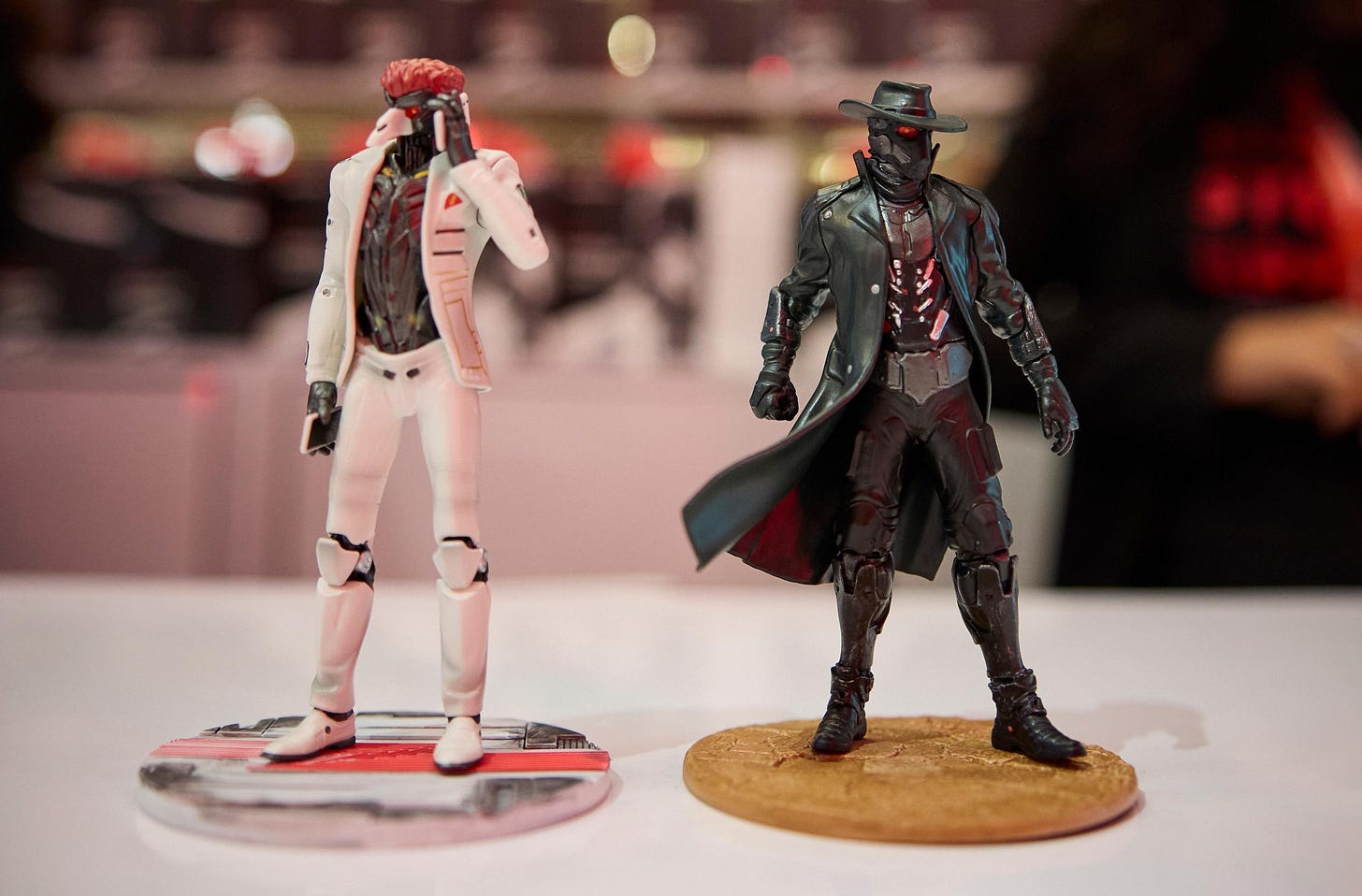

military threat to Taiwan.

The military threat comes on the final page in the form of a picture of two aircraft carriers during a 2024 Chinese naval exercise.

Nothing like this has been done anywhere else in a single document. In the West, there would usually be a technical report from a private vendor. It can be followed by an indictment (legal action) and a State Department press-release (a political accusation). Then, an elected official or a representative of the Administration might make some kind of veiled threats.

Although it’s hard to tell exactly how the CVERC/Qihoo 360 report on Taiwanese APTs was put together, we can clearly see the hand of the Chinese government in bringing together these different elements including both private sector expertise, law enforcement action, and military messaging all with the purpose of not only exposing a cyber threat but also of putting pressure on Taiwan in the larger context of cross-strait relations.

Unlike the Netherlands, in this case China didn’t lead with releasing threat intelligence. Rather, it convened and coordinated stakeholders and used it strategically to advance it national priorities.

Conclusion

To sum up, these publications made me think about several avenues for the nationalization of cyber threat intelligence:

Firms aligning their business priorities with home government’s national security agenda;

Governments seeking to standardize threat actor attribution;

Governments becoming the source of threat intelligence;

Governments combining private threat intelligence with government action to achieved strategic goals.

It doesn’t seem that we are nearing the end of private threat intelligence but these mechanisms could probably make this field more and more nationalized. The nationalization primarily affects the public side of threat intelligence, but in other respects it will remain global as long as we have the Internet and the whole world uses basically the same technologies. For instance, for cyber threat researchers it makes no sense to stick to the nationalized priorities—they would still absorb as much information from across the world, since threats are not limited by borders and threat actors learn from each other fast. But when it comes to putting stuff out, they already have to take into account not only business and community interests but also national considerations.